Photographs: Rediff Archives and Reuters

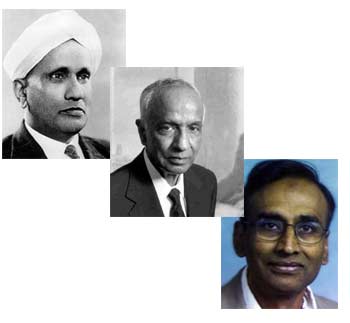

In an interview to rediff.com's Shobha Warrier in Chennai, he discusses if there is a link between exemplary scientific research and being Tamil Brahmin against the background that three Indian scientists (Sir C V Raman, Dr Subramaniam Chandrasekhar and Dr Venkataraman Ramakrishnan) to win the Nobel Prize for the sciences have been Tamil Brahmins.

Three of the Indian Nobel Prize winners in science hail from Tamil Nadu and all of them are Brahmins. Do you see any connection between scientific research and Tamil Brahmins?

The term 'Tamil Brahmin' sounds a bit parochial and casteist. On the basis of three prizes, which are too small in number, it is difficult to judge its linkage with a community. What is seen as a co-relation may be sheer coincidence.

We also see a co-relation between the Nobel Prize and Jews as most of the Nobel Prize winners are from a Jewish background. Nevertheless, we cannot overlook the crucial importance of cultural capital in intellectual achievements; and virtually all the Nobel Prize winners possessed cultural capital.

In one sense, you can use the genes theory -- genetically some groups are advanced. But that may not happen in a hierarchical society, and ours has always been a hierarchical society.

Why do you say that in a hierarchical society, the gene theory won't work?

It can only happen randomly. In a hierarchical society, the cultural capital is concentrated at the top. Brahmins are at the summit of the social hierarchy. So, they had all the advantages of society traditionally, though they may not be having the same advantages now.

Cultural capital gets transmitted from generation to generation and over generations, this transmission makes its recipients well-entrenched.

As early as the 1880s, the British administration had reported that a poor Brahmin cannot be compared to a poor untouchable for the simple reason that the poverty of a Brahmin is only economic, but the poverty of an untouchable is both economic and cultural.

Brahmins have cultural capital. That is also the reason that where talent has to be used persistently and assiduously, Brahmins have been shining. It is not that others are dullards. Universally, intelligence is distributed across the entire society. But opportunities are not.

If you take the Nobel Prize winners from India, most of them are confined to Tamil Nadu and Bengal. Do you have a sociological interpretation to that?

Not really. All the same, it is important to keep in mind that the social background of Brahmins in these states has been rich and aristocratic.

You mean they were not so rich in other states?

In the south, except in Kerala, the Brahmins lived an aristocratic life. In Kerala, what happened was the Namboodiri families initially refused to take to English education because of superstition. It took them some time to come out of it.

If you take all of India, Brahmins were the first to take to English education, and gradually managed to monopolise it. Brahmins had a monopoly over indigenous education also. But by taking to English education, they abandoned indigenous education and allowed it to have a natural death.

'Brahmins have cultural capital'

Image: Young Brahmin boysPhotographs: Amit Dave/Reuters

Yes, they did. But gradually the non-Brahmin upper castes confronted the British and managed to break the Brahmin monopoly. However, this did not help the lower strata of society, particularly the untouchables whom all the Savarnas or castes of the four-fold Varna system (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaisyas, and Shudras) excluded from society and its benefits. This situation continues even now.

One thing is important to recall here. Initially, the Brahmins refused to have anything to do with medical education as that involved physical contact with other castes.

Is that the reason they went in for pure science and scientific research?

That came much later. They took to English education and they were the first to take literature and engineering which was not science education then. That was around 100 years ago. Whatever it is, their mind was very much embedded in the knowledge system.

Has it anything to do with their cultural position?

Cultural and social positions are inseparable. Brahmins were at the top of society. They were the 'Lotus eaters' and the leisure class. They had ample time to read, write and engage in cultural activities.

Was the life of the Brahmin in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka different from that of the Brahmin in other parts of India?

It was not similar. The Brahmin population in south India has been very small and south India did not have the Varna categories of Kshatriya (the warrior class) and Vaisya or Baniya (the business class). It had only the categories of Brahmin and Shudra, though by pleasing the Brahmin (priestly class) and later pleading to the British, the Kshatriya and Vaisya categories emerged.

In northern India, equally competent were the Baniyas. They dominated both education and trade whereas in south India and eastern India (Orissa and Bengal), Brahmins were the only aristocratic class.

If Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen has been a great scholar, it is partly because of his background. For generations, his family has been aristocratic. He hails from a distinguished landed family. His maternal grandfather was a renowned scholar and a close associate of Rabindranath Tagore in Shantiniketan.

Sen had all the comforts and conveniences in life to nurture his brain and engage in the pursuit of knowledge.

The same was the case with Tagore too; he was an aristocrat. That is why I said cultural capital is crucial for intellectual pursuits and attainments.

Only a few persons like E M S Namboodiripad in Kerala used education for serving society. As you may know EMS turned a revolutionary and brought in the first democratically elected Communist government in Kerala, the first thing to happen anywhere in the world.

In the rest of south India, serving society has never been part of the Brahminical mindset.

You cannot condemn a hard working person because of his background; all the same, it is important to note that his achievements in life are certainly linked to his cultural capital. Only the privileged class has cultural capital.

'The Dravidian movement did not have any effect on Brahmins'

Image: Shiv Nadar, Chairman, HCL TechnologiesPhotographs: Photograph courtesy: HCL Technologies, Dr Radhakrishnan's photograph: Sreeram Selvaraj

The Dravidian movement did not have any effect on Brahmins. It was a historical and political farce; it did not happen. It was an educated, non-Brahmin, upper caste movement against the Brahmins.

These castes wanted to get rid of the Brahmins from their monopoly in education and employment. They succeeded in that. In the process and in their self-interest they left in the lurch the lower castes, in particular the Untouchables. Beyond that, nothing happened in Tamil Nadu.

Of late non-Brahmins, including the lower strata, have become mobile, assertive and aspiring. They don't have to wait for a century to make their mark in society, particularly by gaining cultural capital.

Will we see more of non-Brahmins in the field of knowledge?

Yes. Knowledge has become an industry now. Earlier, it was knowledge for knowledge sake; not any more.

Does that mean knowledge will be open to everybody?

Yes, in theory, it is open to everybody. In another two decades or so, it may happen in practice also. In Tamil Nadu, the upper non-Brahmins always had access to knowledge. And the lower ones also are gaining.

You take the case of HCL; it is headed by a Nadar. Nadars have been very a dynamic caste group that a lot of them have reached the top.

Brahmins are any way a minuscule community; they are less than 3 per cent in Tamil Nadu.

Will you say the monopoly of Brahmins in knowledge is over?

Will you say the monopoly of Brahmins in knowledge is over?

Yes. I will not say that there is no relation between community and scientific work. In the Indian context, certain communities are still in a privileged position.

Do you feel the Dravidian movement resulted in the migration of Brahmins to other places?

The outcome at that time was, many Brahmins moved out of Tamil Nadu to other places. But wherever they went, they carried with them their cultural baggage. If you see the employment data of Tamil Nadu, you may not see many Brahmins in government service; but you certainly see them in the all India services.

In fact, they dominate all the modern, the information and technology-driven professions. So what they lost in the wind (in government service, as a result of the non-Brahmin movement) they gained in the wave.

The Dravidian movement did not erode the cultural capital of Brahmins in any way.

Tamil Brahmins call themselves the Jews of India. Do you agree?

It is not true. (E V Ramaswamy Naicker) Periyar's movement created a sense of insecurity in them at that time. But I don't think Tamil society has ever ill-treated them.It is the Brahmins who ill treated the other castes. They looked down upon on everyone who was not a Brahmin. This attitude continues even now, albeit to a limited extent.

article