P Rajendran reports from New York on a new American study that reveals how India's groundwater resources have depleted alarmingly.

P Rajendran reports from New York on a new American study that reveals how India's groundwater resources have depleted alarmingly.

Imagine water contained in a pure cube of ice 10.4 kilometres high. That is the amount of stored groundwater India has used up in six years in the states of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan. That water has not been replaced.

"That's more than three times the size of Lake Mead, the largest man-made reservoir in the United States," says Jay Famiglietti, a researcher at the University of California-Irvine.

In a paper published in Nature magazine, Famiglietti and Isabella Velicogna, two professors at the University of California-Irvine, and Matt Rodell, of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center, pointed out that this huge amount of water does not include the water found on the surface.

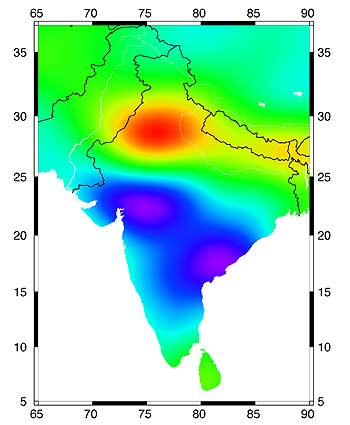

While there is a sharp drop in north-western India, there is an increase in groundwater in south India, although experts pointed out that this is not as significant as it appears.

"When you think about groundwater depletion, it's like a bank account; you've got inflows, you've got withdrawals, and you've got deposits. When the deposits are greater than the withdrawals, the balance goes up," says Professor Famiglietti.

There was no sharp drop in rainfall between 2002 and 2008, the period over which the study was conducted, and so the drop in groundwater levels was most likely caused by irrigation, he says.

That view is backed by John Briscoe, professor of the Practice of Environmental Health at the Harvard School of Public Health, and the co-author of India's Water Economy, a 2006 book that warned about a future water crisis in India. But he pointed out that the use of groundwater was not always a bad thing.

The British modernised the water system and introduced a system of canals that worked till the 1950s, when groundwater pumps were improved, says Professor Briscoe.

The leaky canals, like those headed out from the Bhakra Nangal project, recharged the underground reservoirs but, until then, the suction pumps available then could lift water up only about 6 metres, he says. So the farmers had to keep a corrupt irrigation department happy to get their share of the canal water.

"In the 1960s, tubewells started a fantastically positive revolution," Professor Briscoe says, adding that these powerful pumps had the benefit of also reducing salinity, a change that was good for the crops.

The politicians soon made it part of their policy to subsidise electricity for farmers. But while a small drop in the groundwater -- which is recharged over centuries -- was a good thing, it was not as good when millions of farmers started sucking up the water, encouraged by the presence of cheap and powerful pumps, he says.

An index of the change is the increase in the number of 'black blocks,' areas where groundwater levels have dropped below safe levels. According to Professor Briscoe, in Rajasthan, these 'black blocks' made up 17 per cent of the state about 10 years ago; now it covers 60 per cent.

According to Tushaar Shah, a senior fellow at the International Water Management Institute who works in Saurashtra, one problem is that while the population is increasing, the arable land sustaining it is essentially the same. It is common to see three crops being wrested out of a piece of land instead of one.

Irrigation is important even during winter and summer, when there are no rains to feed reservoirs above and below the ground.

Professor Briscoe also pointed out the concept of 'virtual water,' or the amount of water needed to grow a particular crop. For example, it takes 1,000 tons of water to produce one ton of wheat. While it makes sense to have water-intensive crops exported from areas with more water resources to those with less, in India the situation is flipped, he says.

The result is that more 'virtual water' is flowing from areas with less water to areas with more water. All this is, of course, not to argue that the world's water levels are dropping -- they are maintained by the water cycle -- just that the management of the available fresh water is inefficient, that there is less water on and under the land to sustain the population.

According to Professor Famiglietti, as in the rest of the world, irrigation in India is only about 30 per cent efficient. So improvement in infrastructure and delivery is important.

For instance, he says, it is better to not let pumped water spray out, to time the irrigation for a time in the day or year when evaporation is reduced, and to irrigate only as much as the soil needs.

"We have tools in place to actually monitor the groundwater withdrawal," says Professor Famiglietti. "We can help water managers make decisions about things like irrigation and water distribution because we can see how storage is changing over a very large area that may not be apparent from (studying) a subset of wells."

The tools Professor Famiglietti is talking of includes the gravitation measuring NASA satellites he used to collect the data. While orbiting the earth about 137 miles from each other, each measures its distance from the other.

As each passes over areas of higher gravitation, it slows down, increasing the distance from its twin. The scientists calculated the changes in gravitation on the earth over time and concluded that it was correlated primarily with changes in water levels. And that is how they found the water levels had dropped precipitously in north-western India.

But monitoring alone is not enough. A study led by V N Sharda of the Central Soil and Water Conservation Research and Training Institute, Dehradun, and published in the Journal of Hydrology, estimated that it takes 104 mm of rain to increase groundwater by 1 mm.

Saurashtra has found one way to circumvent this alarming statistic, says Shah.

After a drought in 1987, religious leaders, primarily from the Swaminarayan sect and the Swadhyay Parivar, told local farmers not to look to the government for help, but build check dams to store water.

According to Shah, between 1990 and 2000, 100,000 check dams and about the same number of percolation ponds were set up. Even given a reluctant rate of recharge, enough water trickled down to significantly increase the groundwater available.

In Saurashtra, the increase in water levels is clearly visible coming atop the shallow hard rock substrate. But the alluvial soil deposits in places like Punjab and Haryana tend to get waterlogged and, being far deeper and far wider than those in Saurashtra, the increases in water level are less dramatic, says Shah.

Although, as Professor Briscoe points out, the Gangetic basin is home to the biggest underground reservoir in India, Shah says India has the advantage of having 65 per cent of its aquifers in hard rock areas.

Non-governmental groups like the Dhan Foundation in Madurai district in Tamil Nadu, and the Hirwe Bazaar have successfully worked to get people to recharge the groundwater in their area, instead of using up the storehouse of centuries in a few decades.

Until the time it becomes accepted practice, much of the world will have to go short on water -- and even risk water conflicts in the bargain.

Image: The NASA image showing depletion of groundwater in north India | Photograph: Isabella Velicogna/NASA

Related links: 'Water shortage is a very, very serious situation'

Coming soon: The war for water!

Most Indian cities to go dry by 2020