Image: Pakistan President Zardari is unable to change the power equations in his country

Photographs: Caren Firouz/Reuters

Photographs: Caren Firouz/Reuters

Former diplomat M K Bhadrakumar recently presented a paper on Pakistan and Terrorism at the Asia Centre, a Bangalore-based think-tank.

- There is little or no evidence that the return to representative rule in Pakistan last year means the supremacy of civilian government. The so-called permanent establishment remains in place -- the military, top echelons of bureaucracy and the intelligence agencies. The army continues to be in the driving seat with regard to foreign and defence policy, internal security and nuclear policy.

- It is a fallacy to look for 'rogue elements' within the Inter Services Intelligence or assume that ISI is a 'state within a state.' The ISI is under military control and it serves as the military's instrument. The ISI may have operational freedom but cannot conceivably act against the military interests. The military operates as a coherent organisation. There are no 'factions' within it.

- The polarisation between the Pakistan Muslim League and Pakistan People's Party remains acute. Worse, religious parties act as hand-maidens of the establishment. The influence of civil society should not be exaggerated.

- Finally, the military's corporate interests lie in preserving its political (and growingly economic) prerogatives and the power and privileges it accumulated by claiming to be the custodians of the Pakistani State

'ISI will keep backing militants'

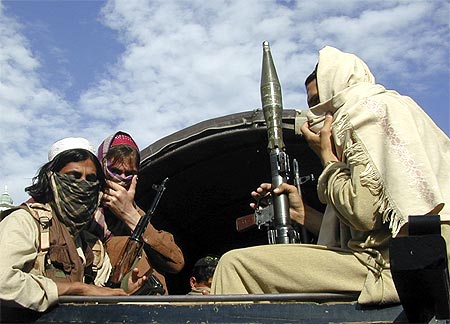

Image: The Taliban are a strategic asset for the Pakistani military- The million-dollar question is the extent to which the military and the ISI continue to extend covert support to the militants. The answer is that they will continue to support militant groups that serve Pakistan's regional interests.

- The military will be harsh on those groups that threaten Pakistan's territorial integrity. No question of military tolerating sub-national groups threatening Pakistani secession, either. However, the military visualises that the jihadi groups, which serve its purposes regionally or internally, are ultimately controllable and calculable.

- The military's animus against India will not easily mellow. It is inclined to see things through India-tinted lens. There is deep-rooted suspicion about Indian intentions, compounded more recently by apprehensions of Indo-US collusion or strategic alliance; acute insecurities borne out of India's weapons purchases; suspicions over perceived Indian influence in Afghanistan and meddling in the Pakistani domestic scene by the Indian agencies.

- These fears are bound to grow, not lessen. Which suggests that there is compelling reason for the military not to abandon its reliance upon militant or jihadi groups for the foreseeable future.

- The Taliban are a strategic asset for the Pakistani military, especially in a situation where US forces may abruptly decide to vacate Afghanistan. After all, apart from the concerns regarding the Indian presence in Afghanistan (which may be tendentious or real), Pakistan has legitimate interests in Afghanistan.

What is America's priority?

Image: President Obama is encouraging other relevant States to get engaged in stabilising Pakistan- The US priority currently is to expand its leverage on Pakistan, given the dependence on it in the war in Afghanistan. This translates as several elements. One, Obama has held out a new assistance paradigm civilian and military that envisions Pakistan's future in the medium term.

- Two, Obama has shown an extra willingness to take into account Pakistan's regional perceptions and legitimate concerns, which can manifest as: a. restraint in recognising Indian's pre-eminence in the region; b. greater attention to India-Pakistan tensions; c. urgings to robustly pursue composite dialogue, including the Kashmir issue; and, d. accommodation of Pakistani interests in Afghanistan via a lowering of the Indian profile in Kabul.

- Three, Obama is encouraging other relevant States to get engaged in stabilising Pakistan, China and Saudi Arabia and the European countries, in particular. The US invitation to China has far-reaching implications.

- Four, there is evidence that the US has misgivings about the Pakistani political elite's grasp of the crisis, its competence, performance and even the capacity to rise above sectarian politics for short-term gains. Quite obviously, the US overwhelmingly depends on the Pakistani military to deliver and it will be truly a miracle if it introduces conditionality on military aid to Pakistan.

- Five, the US does not contemplate a containment strategy towards Pakistan being the 'epicentre' of international terrorism, as many Indians like to project.

The Afghan factor

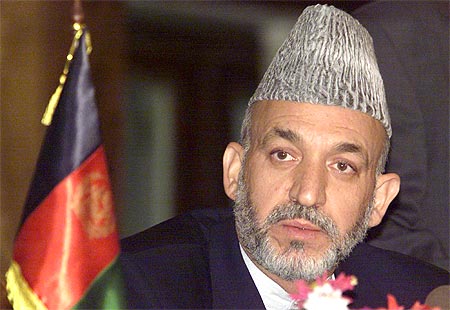

Image: Afghanistan President Hamid KarzaiPhotographs: Romeo Ranoco/Reuters

- There is a stalemate. The Taliban cannot capture power but the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, NATO, cannot defeat the Taliban. US Defence Secretary Robert Gates said the Taliban have the upper hand at present and that the timeline is short for reversing the tide as US opinion may turn against the war. Clearly, the 12 to 18 month period ahead becomes extremely critical. Barack Obama's re-election campaign by end-2010 or early-2011 is bound to introduce new compulsions.

- There is very little interest on the part of major NATO powers to increase their troop commitments. Thus, the bulk of fighting will need to be borne by US forces.

- The surge strategy essentially involves stepping up of pressure on Taliban fighters within southern Afghanistan and pushing them toward the Pakistan border region so that the Pakistan military would squeeze the militants from their side simultaneously. Alongside, a political track will involve hammering the irreconcilables hard and segregating the reconcilables. A so-called bottoms-up approach is envisaged province-by-province on the pattern of the Awakening in Iraq.

- An altogether separate track is running, unacknowledged by the US, in terms of negotiations with the hardcore Taliban leadership and Afghan rebel leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Meanwhile, Afghan President Hamid Karzai also pursues his contacts with the Taliban. Unclear where, when or how the various tracks will meet, if at all. The Saudis are certainly in it and the ISI plus the ubiquitous British intelligence.

- Obama has spoken of regional initiatives. But geopolitics remain muddled question marks linger over re-setting US-Russia relations; Russia and China oppose NATO expansion into Central Asia; a US-Iran standoff is in a state of animated suspension; India-Pakistan tensions spill over into the Hindu Kush; energy rivalry.

What does it mean for India

Image: India should be highly wary of developments in Pakistan

For India, there are pluses and minuses.

India's drawbacks are:

- The US policy is a replay of past approaches relying on military aid to create leverage with the Pakistan army.

- The US military assistance boosts Pakistani capability.

- Assumptions of any basic change in the Pakistani military's mindset are premature.

- The US priorities and the Pakistan's army's priorities diverge. Therefore, the AfPak strategy's efficacy remains doubtful.

- Deeper US involvement in the region is resented by Pakistani public opinion, and it provides a breeding ground for militant groups. But the US sidesteps this core issue.

- Pakistan's stability is linked to the Afghan war. So long as the war continues, Pakistan will remain in a state of extreme turbulence.

- The adage that the Pakistani temper is of moderate Islam may not hold anymore, as there is a creeping Islamisation in public attitudes and lifestyles. The Afghan war is radicalising the Islamic groups.

- Ethnic fault lines are surfacing, putting question marks on Pakistan's stability. Any slide toward a balkanisation of Pakistan under any circumstances will have catastrophic consequences for India's security.

- The US may increasingly feel the need to intervene in India-Pak relations by way of appeasing the Pak military.

- The US almost certainly expects a rollback of the Indian presence in Afghanistan.

- The US may accommodate the Taliban in the power structure in Kabul, no matter India's opposition.

- Richard Holbrooke, President Obama's special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, has sought China' help. This may well herald a broader US-China understanding on region.

- Pakistan is being drawn into Western alliances like NATO and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

- Obama's regional policies belie Indian expectations of being recognized by the US as the pre-eminent power in the region. At the end of the day, India is an important power in the region like Pakistan, which directly impacts on the US's national security interests. A de-facto hyphenation with Pakistan in US policies is quite apparent. This, along with the rapidly expanding broader US-China ties (against the backdrop of the economic crisis) indeed puts a question mark on our assumptions of emerging as a balancer in the international system.

What is India's advantage?

Image: The Mumbai attacks have changed the world's perception of PakistanPhotographs: Arko Dutta/Reuters

However, India has many advantages. They are:

- Pakistan's conduct vis-a-vis terrorism is under international scrutiny. This may perhaps put a break on ISI activities against India.

- Stabilising Pakistan; moderating the Pakistani military's attitudes and doctrines; defanging the militant groups; and severing the military's links with the militants these are no doubt positive things to happen if the US indeed succeeds.

- Pakistan's military is increasingly tied down in the Afghan border regions. This reduces its capacity to foment tensions in Jammu and Kashmir. A relative calm exists in J&K.

- Clearly, India needs to energise its moribund regional diplomacy. Relations with Russia and Iran have lost their elan. Greater attention should also be paid to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. India has much in common with the SCO countries as regards issues of terrorism, religious extremism and separatism, and regional stability.

- Most important, we must take note that China is a vastly different power today as compared to a quarter century back. Who would have thought the Chinese Communist Party felt it desirable to sign an Memorandum of Understanding and forge an institutionalised relationship with the RSS? Plainly put, not all that China does in its relationship with Pakistan arguably, much of it is necessarily borne out of animus against India.

- The big question is whether we can constructively engage China on regional issues such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, etc. rather than remain fixated on the dubious string-of-pearls doctrine crafted by a junior ex-Pentagon analyst in her late twenties that Chinese policies single-mindedly work to isolate India in the region.

article