Political parties, including the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party, are keeping their fingers crossed over the verdict's possible fallout, an issue that has engaged Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's attention.

Let's go back in time to see how it all began.

When was the first legal claim made over the Babri Masjid?

The first suit in the matter was filed on January 19, 1885.

It sought to gain the right over the chabootra (raised platform) for the plaintiff, Raghubar Das.

...

What Judge Chambier ruled in 1886

Image: Security personnel in AyodhyaWhat was the outcome of that case?

In his order dated February 24, 1885, the judge declined permission on the ground that, even though the land on which the chabootra stood belonged to the plaintiff, 'it was so close to the existing masjid that it would be contrary to public policy to grant a decree authorising him to build a temple as desired by him.'

The Faizabad sub-judge who came to this decision was Pandit Hari Kishan, a Brahmin.

Das then appealed to Faizabad's district judge, Colonel J E A Chambier, who, after a spot inspection on March 17, 1886, dismissed the appeal on the same grounds.

The Englishman also struck down the part of the sub-judge's verdict which conceded the property to Das.

Judge Chambier ruled: 'I found that the masjid built by Emperor Babar stands on the border of the town of Ayodhya... It is most unfortunate that a masjid should have been built on the land specially held sacred by the Hindus. But as it occurred 356 years ago, it is too late now to remedy the grievance. All that can be done is to maintain the parties in status quo.'

He went on to observe: 'This chabootra is said to indicate the birthplace of Ram Chander... A wall pierced here and there with a railing hides the platform of the masjid from the enclosure in which stands the chabootra.'

Oudh judicial commissioner W Young disputed the mahant's claim

Image: Image used for representational purposes'The Hindus seem to have got very limited rights of access to certain spots within the precinct adjoining the mosque and they have, for a series of years, been persistently trying to increase those rights and to erect buildings on two spots in the enclosure, namely Sita ki rasoi (Sita's kitchen) and Ram Chandra ki janmabhoomi.'

Upholding the earlier decisions, the judicial commissioner only disputed the mahant's claim to ownership of the chabootra.

When did the issue flare up again?

The District Gazetteer of 1905 confirmed that both Hindus and Muslims were offering prayers in the same building until 1855.

'Since the mutiny of 1857, an outer enclosure has been put up in front of the mosque and the Hindus, who are forbidden access to the inner yard, make their offerings on a platform (chabootra) which they have raised in the outer one.'

Issue flared again in 1949

Image: A Shiv Sena demonstration in favour of the Ram templeNothing significant was reported over the next 48 years until 1934, when a communal flare-up over the slaughter of a cow in a neighbouring village provoked an attack on the Babri Masjid.

Some damage was caused to one of the three domes of the mosque; it was later repaired at government cost.

Thereafter, all was quiet until the night of December 22, 1949, when the idol of Lord Ram was placed in the mosque, following which hundreds of Hindus arrived and started offering prayers.

Even though the crowds were pushed back and the mosque's gates were padlocked, the deity remained inside.

Why was the idol not removed thereafter?

No one dared to move it, despite a directive to do so from then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru to then Uttar Pradesh chief minister Gobind Ballabh Pant.

Then district magistrate K K K Nayyar expressed his inability to get the idol removed; he said he would prefer to be relieved of the charge rather than carry out the orders.

None dared to remove the idol

Image: Security personnel in AyodhyaHe also said, 'It would not be wise to stop the bhog and aarti at the spot where the deity was placed,' and added, 'I think that, with the lapse of time, the present excitement will wear off and it would then be possible to evolve some satisfactory and enduring plan to end this dilemma.'

For some time, it seemed everyone was satisfied with the status quo and, by December 29, 1949, the additional city magistrate ordered attachment of the property. Then local municipal board chairman Priya Dutt Ram was appointed the receiver.

Then came the next round of legal battles...

On January 16, 1950, a suit was filed by a local resident, Gopal Singh Visharad, before Faizabad's civil judge, seeking permission to offer prayers inside the mosque where the deity of Lord Ram had been placed.

Civil judge N N Chadha passed an interim injunction, with the rider that the public could not be allowed to freely offer puja or receive darshan. But the local priest was allowed to perform the daily bhog.

More claimants emerge, Muslims respond

Image: A scene from AyodhyaHe also confirmed that the 'idols of Shri Ram were surreptitiously and wrongly put inside.'

How did the Muslim community respond?

The ownership of the land, though, remained disputed as another local Hindu congregation, the Nirmohi Akhara, also staked its claim over it.

The following year, five Muslims from Ayodhya led by Mohammad Hashim moved a petition before the high court, seeking a vacation of the injunction.

In 1955, a division bench of the Allahabad high court ruled that the status quo needed to be maintained, but expressed the need for a final decision to be taken within six months, 'in view of the seriousness of the matter.' But nothing happened.

Six years later, in 1961, Mohammad Hashim filed another suit pleading for restoration of the property to the Muslims.

By 1964, the peripheral cases were settled and a date was fixed for the final hearing of this case.

To this end, a new receiver was appointed in 1968. However, his role became redundant as yet another appeal was filed before the Allahabad high court in 1971.

VHP gets serious, launches movement

Image: Image used for representational purposesThe 1971 case was not taken up until 1983, when the VHP launched its temple movement in a big way.

Even as the tempo of the temple movement increased, then Faizabad district judge K M Pandey ordered the gates of the disputed site to be unlocked late in the afternoon of February 1, 1986.

This was done on an application moved by local lawyer U C Pandey, who sought permission to offer prayers.

Simultaneously, VHP leaders S N Katju, Deoki Nandan Agarwal, both of whom were former Allahabad high court judges, and Shirish Chandra Dikshit, former UP director general of police, met the district magistrate, seeking permission for Lord Ram's darshan.

Judge Pandey observed, 'After having heard the parties, it is clear that the members of the other community, namely the Muslims, are not going to be affected by any stretch of imagination if the locks of the gates were opened and idols inside the premises are allowed to be seen and worshipped by the pilgrims and devotees.'

He also added that the 'heavens will not fall if the locks of the gates are removed.' But that did not hold true; the order sparked off communal clashes.

Following this, the Sunni Waqf Board and the Babri Masjid Action Committee moved the Allahabad high court against the district judge's order.

The shilanyas in 1989 aggravated the issue

Image: Security personnel in AyodhyaMeanwhile, all cases pertaining to the Ayodhya dispute were referred to the court's Lucknow bench.

The shilanyas in 1989 further aggravated the issue. The police firing ordered by then Uttar Pradesh chief minister Mulayam Singh Yadav's government on the kar sevaks in 1990 polarised Hindu votes in favour of the Bharatiya Janata Party and brought Kalyan Singh to power in 1991.

Kalyan Singh ordered the acquisition of 2.75 acres of land around the mosque in a bid to show his party's seriousness towards building the temple.

Babri Masjid Action Committee convener Zafaryab Jilani filed yet another writ petition to prevent any kind of construction on the acquired land.

Meanwhile, Delhi-based Aslam Bhure moved the Supreme Court against the acquisition of land.

But the apex court transferred the case to the Lucknow bench, with the directive that the status quo be maintained until the high court decided on the five writs that were, by then, pending there.

December 6, 1992

Image: Muslims protestAll hell broke loose on December 6, 1992 in Ayodhya, with violent Hindu mobs storming the 16th century mosque built by the first Mughal emperor Babur's army commander Mir Baqi.

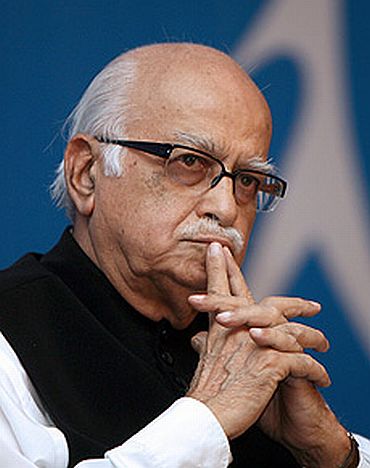

Even as security personnel stood by that fateful day. the mosque was torn down by kar sevaks even as the top BJP leadership -- including L K Advani -- watched.

Advani later expressed sorrow at the demolition -- but it was clear to all that the forces unleashed by his rath yatra in favour of the temple in 1990 would be satisfied with nothing else.

Violence followed the demolition

Image: Kalyan Singh, then Uttar Pradesh chief ministerThe demolition of the mosque on December 6, 1992, led to a contempt of court petition against the UP government.

Then chief minister Kalyan Singh had given the court an undertaking that the mosque would be protected. Kalyan Singh was later awarded a day's imprisonment.

His government had been dismissed hours after the demolition.

A few days after the demolition, the central government headed by then prime minister P V Narasimha Rao issued an ordinance acquiring 67 acres of land in and around the disputed site.

The Babri Masjid's demolition resulted in horrific riots across the country. Hundreds of people were murdered.

Mumbai and Surat were particularly affected by the violence, scarring thousands of people.

In 1994, the Supreme Court ordered the abatement of all pending suits and nullified all interim orders issued by various courts in the Ayodhya-related cases.

The Supreme Court ordered that the land remain in the central government's custody and the status quo be maintained until the Lucknow bench disposed of the writ petition.

This petition aimed to determine whether a Hindu temple had existed on the disputed site prior to the construction of the Babri Masjid and whether the mosque was built on the debris of a temple.

Demolition: 'Neither spontaneous nor unplanned'

Image: L K Advani, architect of the BJP's Ram Janambhoomi movementAmong those charge-sheeted were leaders from the BJP, VHP, Shiv Sena and Bajrang Dal. Prominent among them were L K Advani, Dr Murli Manohar Joshi, Uma Bharti and Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray.

The M S Liberhan Commision probes the demolition

The commission was set up 10 days after the demolition and took 17 years and 48 extensions before it submitted the report on June 30, 2009.

Negating the theory handed out by Hindu groups that the Babri Masjid demolition was mob-driven, the Liberhan Commission said it had been 'established beyond doubt' that the events of December 6, 1992, in Ayodhya were 'neither spontaneous nor unplanned.'

The Commission blamed the entire temple construction movement on the Sangh Parivar.

A former high court judge, Justice Liberhan called former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Advani and Dr Joshi 'pseudo-moderates' and condemned them for their role in the demolition.

'It stands established beyond doubt that the events of the day were neither spontaneous nor unplanned nor an unforeseen overflowing of the people's emotion, nor the result of a foreign conspiracy as some overly imaginative people have tried to suggest,' the 1,029-page report said.

'These leaders have violated the trust of the people'

Image: Image used only for representational purposesAbout Vajpayee, Advani and Dr Joshi, the Liberhan report said: 'These leaders have violated the trust of the people and have allowed their actions to be dictated not by the voters but by a small group of individuals who have used them to implement agendas unsanctioned by the will of the common person.

When is the verdict in the case due?

The special full bench of the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad high court, comprising Justice S U Khan, Justice Sudhir Agarwal and Justice Dharmveer Sharma, was slated to deliver the verdict at 3.30 pm on September 24.

However, the Supreme Court on September 23 put off by a week its hearing into a plea to defer the Ayodhya title verdict by the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad high court.

Supreme Court judge, Justice R V Raveendran, gave this order while hearing the petition filed by retired bureaucrat Ramesh Chand Tripathi to defer the title suit verdict.

In the petition filed through advocate Sunil Jain, Tripathi had cited several reasons for deferment of the verdict, which he said would be in "public interest" in view of the apprehension of communal flareup, upcoming Commonwealth Games, elections in Bihar and violence in Kashmir Valley and Naxal-hit states.

The Supreme Court on September 28 dropped Tripathi's plea and posted the date of the verdict in the case for September 30, 2010.

Also read: What to expect from the verdict

article