Photographs: Wikimedia Commons

American scientists claim to have identified a gene that seems to be a key contributor to the onset of depression, an "exciting" finding that could pave the way for new class of antidepressants.

Depression is a common mental disorder characterised by depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, feelings of guilt or low self-worth.

Although it's among the leading causes of disability worldwide, scientists have been so far unable to pin down the cause of the condition. More over, as many as 40 per cent of depressed patients do not respond to currently available medications.

Now, researchers at the Yale University who found the depression-triggering gene said their discovery would lead to the development of new drugs for this condition, which affects about 121 million people worldwide.

...

MKP-1, the depressing gene

For their study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, researchers led by Professor Ronald S Duman carried out whole genome scans on tissue samples from 21 deceased individuals who had been diagnosed with depression.

Then they were compared with the gene expression levels of 18 other individuals who had not been diagnosed with depression. They found that one gene called MKP-1 was increased more than two-fold in the brain tissues of depressed individuals.

This was "particularly exciting", said the scientists, because the gene inactivates a molecular pathway crucial to the survival and function of neurons and its impairment has been implicated in depression as well as other disorders.

"This could be a primary cause, or at least a major contributing factor, to the signalling abnormalities that lead to depression," said Prof Duman.

Duman's team also found that when the MKP-1 gene is knocked out in mice, the mice become resilient to stress. When the gene is activated, mice exhibit symptoms that mimic depression.

Click on NEXT to read about the mice that can 'smell' light...

A light 'smelling' mice

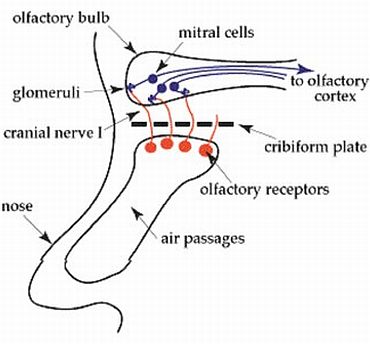

Image: Venkatesh N MurthyPhotographs: Courtesy Harvard University

A team of neurobiologists led by an Indian-origin scientist has claimed to have created a mice that can "smell" light -- a potent new tool that could help researchers better understand the neural basis of olfaction or the sense of smell.

The research, published in journal Nature Neuroscience, has implications for the future study of smell and of complex perception systems that do not lend themselves to easy study with traditional methods.

"It makes intuitive sense to use odours to study smell," said Venkatesh N Murthy, professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University.

"However, odours are so chemically complex that it is extremely difficult to isolate the neural circuits underlying smell that way," he said.

For their study, Murthy and his colleagues at Harvard and Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory used light instead, applying the infant field of optogenetics to the question of how cells in the brain differentiate between odours.'What if we make the nose act like a retina?'

Optogenetic techniques integrate light-reactive proteins into systems that usually sense inputs other than light.

Murthy and his team integrated these proteins called channelrhodopsins into the olfactory systems of mice, creating animals in which "smell pathways were activated not by odours, but rather by light".

"In order to tease apart how the brain perceives differences in odours, it seemed most reasonable to look at the patterns of activation in the brain," Murthy said.

"But it is hard to trace these patterns using olfactory stimuli, since odours are very diverse and often quite subtle. So we asked: What if we make the nose act like a retina?"

With the optogenetically-engineered animal, the scientists were able to characterise the patterns of activation in the olfactory bulb -- the brain region that receives information directly from the nose.

Timing of the 'sniff' plays a large part in how odours are perceived

Because light input can easily be controlled, they were able to design a series of experiments stimulating specific sensory neurons in the nose and looking at the patterns of activation downstream in the olfactory bulb.

"The first question was how the processing is organised, and how similar inputs are processed by adjacent cells in the brain," Murthy said.

But it turns out that the spatial organisation of olfactory information in the brain does not fully explain our ability to sense odours, he added.

The temporal organisation of olfactory information sheds additional light on how we perceive odours. In addition to characterising the spatial organisation of the olfactory bulb, the new study showed how the timing of the "sniff" plays a large part in how odours are perceived.

The study has implications not only for future study of the olfactory system, but more generally for teasing out the underlying neural circuits of other systems.

Click on NEXT to read how a moon can help weigh a distance star

Weighing a star with a moon

Astronomers generally weigh a distant star using computer models, which yields only an estimate. Now, a US scientist has claimed using a new method a star can be "weighed directly" with the help of a moon.

If the star has a planet and that planet has a moon, and both of them cross in front of their star, then we can measure their sizes and orbits to learn about the star, said David Kipping, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics in Cambridge, UK.

Astronomers have found more than 90 planets that cross in front of, or transit, their stars. By measuring the amount of starlight that's blocked, they can calculate how big the planet is relative to the star.

But they can't know exactly how big the planet is unless they know the actual size of the star. Computer models give a very good estimate but not the real measurement.

It's more accurate than computer models

Kipping realised that if a transiting planet has a moon big enough to see (by also blocking starlight), then the planet-moon-star system could be measured in a way that lets us calculate exactly how large and massive all three bodies are.

"Basically, we measure the orbits of the planet around the star and the moon around the planet. Then through Kepler's Laws of Motion, it's possible to calculate the mass of the star," explained Kipping.

The process isn't easy and requires several steps. By measuring how the star's light dims when planet and moon transit, astronomers learn three key numbers: the orbital periods of the moon and planet, the size of their orbits relative to the star, and the size of planet and moon relative to the star.

Plugging those numbers into Kepler's Third Law yields the density of the star and planet. Since density is mass divided by volume, the relative densities and relative sizes gives the relative masses.

Method may soon be put into practice

Finally, scientists measure the star's wobble due to the planet's gravitational tug, known as the radial velocity. Combining the measured velocity with the relative masses, they can calculate the mass of the star directly.

"If there was no moon, this whole exercise would be impossible," stated Kipping. "No moon means we can't work out the density of the planet, so the whole thing grinds to a halt."

Kipping hasn't put his method into practice yet, since no star is known to have both a planet and moon that transit. However, NASA's Kepler spacecraft should discover several such systems.

"When they're found, we'll be ready to weigh them," said Kipping, whose research will appear in the 'Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society'.

Click on NEXT to read about the cannibal T-Rex...

Dreaded T-Rex was a cannibal

Palaeontologists have found evidence that Tyrannosaurus rex, the largest and most dreaded dinosaur that roamed North America 66 million years ago, might have been a cannibal, which sometimes devoured its own species.

The scientists, who based their study on the bite marks on the carnivores' bones, believe the marks were made by other T-Rexes.

The marks suggest that the giants were killed and then eaten out by victorious T-Rexes, the researchers reported in the journal PLoS ONE.

While searching through dinosaur fossil collections for another study on dinosaur bones with mammal tooth marks, Nick Longrich, a researcher from Yale University, discovered a bone with especially large gouges in them.

Given the age and location of the fossil, the marks had to be made by T-Rex, Longrich said. "They're the kind of marks that any big carnivore could have made, but T-Rex was the only big carnivore in western North America 65 million years ago," Longrich said.

'It's a convenient way to take out the competition'

It was only after discovering the bite marks were from a T-Rex that Longrich realised the bone itself also belonged to the behemoth.

After searching through a few dozen T-Rex bones from several different museum fossil collections, he discovered a total of three foot bones (including two toes) and one arm bone that showed evidence of T. rex cannibalism, representing a significant percentage.

"It's surprising how frequent it appears to have been," Longrich said. "We're not exactly sure what that means."

The marks are definitely the result of feeding. If two T-Rex fought to the death, the victor might have made a meal out of his adversary, said Longrich.

He said: "Modern big carnivores do this all the time. It's a convenient way to take out the competition and get a bit of food at the same time."

It's another vital clue in the T-Rex puzzle

However, the marks appear to have been made some time after death, Longrich said, meaning that if one dinosaur killed another, it might have eaten most of the meat off the more accessible parts of the carcass before returning to pick at the smaller foot and arm bones.

While only one other dinosaur species, Majungatholus, is known to have been a cannibal, Longrich said the practice was likely more common than we think and a closer examination of fossil bones could turn up more evidence that other species also preyed on one another.

The finding is a big clue into the obscure eating habits of these enormous predators. While today's large carnivores often hunt together in packs, T-Rex likely acted on their own, Longrich said.

"These animals were some of the largest terrestrial carnivores of all time. There's a big mystery around what and how they ate, and this research helps to uncover one piece of the puzzle."

Click on NEXT to read about the 'silver bullet' against common cold...

Silver bullets to eliminate common cold

Scientists have turned bacteria, found in yogurt, into "silver bullets" which they claim could destroy viruses and provide a cure for flu and common cold.

A team at the University of Ghent in Belgium has, in fact, discovered that it can attach tiny studs of silver onto the surface of otherwise harmless bacteria, giving them the ability to destroy viruses.

The scientists have tested the silver-impregnated bacteria against norovirus -- known to cause 90 per cent of the gastroenteritis cases around the world -- and found that they leave the virus unable to cause infections.

They now believe that the same technique could help to combat other viruses, including influenza and those causing the common cold.

Bacteria used is found in yogurts and probiotic drinks

Prof Willy Verstraete, who led the team, said that the bacteria could be incorporated into a nasal spray, water filters and hand washes to prevent viruses from being spread.

He was quoted by The Daily Telegraph as saying, "We are using silver nanoparticles, which are extremely small but give a large amount of surface area as they can clump around the virus, increasing the inhibiting effect.

"There are concerns about using such small particles of silver in the human body and what harm it might cause to human health, so we have attached the silver nanoparticles to the surface of a bacterium. It means the silver particles remain small, but they are not free to roam around the body."

The bacteria used, Lactobacillus fermentum, is normally considered to be a "friendly" bacteria that is often found in yogurts and probiotic drinks that can help to aid digestion.

The magic of silver ions

The scientists found that when grown in a solution of silver ions, the bacteria excrete tiny particles of silver, 10,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair, which stud the outside of the cells.

Although the bacteria eventually die as a result of the silver, they remain intact and the dead cells carrying the silver particles can then be added to solutions to create nasal sprays or handwashes.

The scientists also found they could be fixed onto other surfaces such as water filters or chopping boards, which can harbour viruses.

The findings have been presented at a meeting of the Society for Applied Microbiology in London.

article