Photographs: Raj Patidar/Reuters

Vinod Raina analyses whether the Right to Education Act, which came into force on Thursday, will be able to meet the triple challenges of access, equity and quality in elementary education.

Even though nearly all educationally developed countries attained their current educational status by legislating free and compulsory education -- Britain did so in 1870 -- India has dithered and lagged behind in introducing such legislation, with grave consequences.

Of the nearly 200 million children in the age group between 6 and 14 years, more than half do not complete eight years of elementary education; they either never enroll or they drop out of schools. Of those who do complete eight years of schooling, the achievement levels of a large percentage, in language and mathematics, is unacceptably low. It is no wonder that a majority of the excluded and non-achievers come from the most deprived sections of society -- Dalits, Other Backward Claases, tribals, women, Muslims and financially backward -- precisely those who are supposed to be empowered through education.

With heightened political consciousness among the deprived and marginalised, never in the history of India has the demand for inclusive education been as fervent as today. Yet, even a cursory examination of the Act shows some glaring shortcomings.

As a signatory to the United Nations Child Rights Convention, India has accepted the international definition of a child as someone under the age of 18 years. The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, which came into force on Thursday, covers only children in the age group between 6 and 14, clearly excluding and violating the rights of the 0-6 and 14 to 18 year olds. This problem can be traced to the 86th Amendment and its Article 21A, which defines the age. It is imperative that the 86th Amendment should have been re-amended to correct this anomaly, but it was not done.

What is 'free' education?

Image: Two girls walk to their school in a Kerala villagePhotographs: Arko Datta/Reuters

Many argue that the Act should have been put on hold till such a re-amendment was passed, but that would be playing into the hands of elements who want neither the amendment nor the Act. Such elements do not want the State to invest in education and persuading Parliament to re-amend it at this stage, with the kind of majority required to do so, seems remote.

Having made education a fundamental right, the question that needs serious debate is whether the Act will help improve the situation in a substantial manner or not. To address that question, it needs to be recognised that the challenge of elementary education is to somehow find a way to deal with the elusive triangle of access, equity and quality. The Act needs to be critically evaluated from the viewpoint of this triangular challenge.

The basic aspect of access is the provision of a school in the proximity of a child, since there are still several areas in the country where such access is lacking. The Act envisages that each child must have access to a neighbourhood school within three years of the Act coming into force. The presence of a nearby school, however, does not guarantee that a child will have access to it. One of the key barriers, particularly for the poor and the deprived, is the issue of cost.

That is where one of the critical aspects of Article 21A comes into play, namely, the State shall provide 'free' education. Normally, 'free' is interpreted as non-payment of fees by the parents of the child. But numerous studies have concluded that the fee constitutes only one of the components of educational expenditure. And since the landless, poor and socially deprived cannot meet the other expenses, it results in the non-participation of their children in education.

These other expenses differ from place to place, but the cost of uniforms, notebooks and textbooks are perhaps common. The bill defines free education to mean any fee, expense or expenditure that keeps a child from participating in education, and obliges the State to provide all these. This broader definition, with implications for higher expenditure by the State, appears to be a better way to meet the challenge of access in terms of costs, rather than providing a list of items that will be covered which are difficult to anticipate in different locations and in the future and hence cannot be exhaustive.

Purchasing education from private profit-making schools

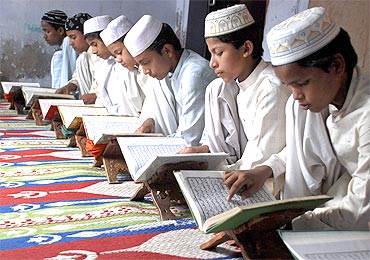

Image: Muslim children read the Quran at a madrassaPhotographs: K K Arora/Reuters

Sustained participation in schooling is, however, equally influenced by the quality of access. The high non-retention rates in spite of higher enrolments in recent years are a clear indication that concerns of quality cannot be postponed till access is guaranteed, as also by the increasing tendency to seek out questionable private schools perceiving their quality to be 'better'.

An increasing number of parents, both urban and rural, despite great financial difficulties, are attracted to the option of purchasing education from profit-making private schools that seem to have external frills of quality and regular presence of teachers.

The Act tries to address the problem by invoking a minimum infrastructural quality in schools through a mandatory schedule which lays down minimum norms for availability of classrooms, libraries, teaching-learning materials, separate toilets for boys and girls, drinking water and playgrounds. The schedule also mandates a minimum pupil-teacher ratio, number of hours of teaching per week and for the year. The Act explicitly requires the pupil-teacher ratio to be maintained in each school, rather than as an average over a block or a district, which allows for a great deal of skewed-ness in the placement of teachers between towns and remote areas.

The most difficult part of the Act to implement will be the provision for appointing teachers, on the basis of national norms, to be determined by a national agency within five years of its notification. Given the extraordinary number of untrained teachers appointed in the last 15 years, state governments will have to completely overhaul teacher training mechanisms to put this provision in place, both in order to bring existing teachers under these norms, and ensure that new teachers are appointed only after they have been pre-trained to these norms. This could be a major factor in determining the future quality of government schools.

Harassment and punishment are explicitly prohibited

Image: School children dressed as Chacha Nehru take part in a fancy dress competitionPhotographs: Raj Patidar/Reuters

Having provided for the salary and emoluments of teachers to be commensurate with these qualifications, the Act lays down duties and responsibilities of teachers in specific terms to ensure their regular presence and engagement with the school. Consequently, it prohibits all non-academic tasks that the teacher may be asked to do, except for duties related to elections and decennial census, which are mandated for all government employees by another Article of the Constitution, and which no Act can override. It is hoped that the infrastructural and teacher quality provisions will reverse the trend of further dilution of the already impoverished government school system.

The management of the school system has been a matter of constant debate, ever since it became apparent that the present highly bureaucratised system could not deliver at the local levels. There is a self-suggesting principle regarding management that has been incorporated in the Act, explicitly bringing in the parents. But even parent teacher associations in good schools normally have no say in the management aspects of the schools; that is the prerogative of a separate management committee.

While recognising the overall role of the local authorities in the management of the schools, the Act mandates that each government school will be managed by a school management committee that will draw three-fourth of its members from among the parents of children in the school, with special emphasis on those belonging to weaker and deprived sections. The SMC shall monitor, plan and manage the school, in collaboration with the local authority.

Even more important for overall quality improvement are aspects of curriculum design and its transaction in the classroom. This is also closely related to the very purpose of education -- the values education should promote, the way children should be treated in the classroom, the medium of instruction and so on. Though in countries marked by high social and cultural diversity, educationists increasingly favour the notion of education of equitable quality as against a hegemonising education drawing on universal qualities, this remains a matter of serious contestation.Democracy, equality and secularism

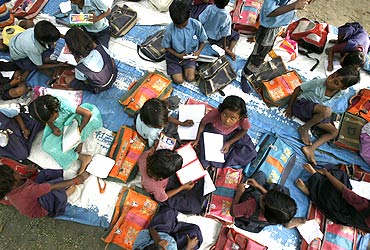

Image: Children at an open air school on the outskirts of New DelhiPhotographs: Parth Sanyal/Reuters

Adherents of market economy and neo-liberal ideologies are impatient with the notion of equitable quality and would instead prefer to see a quick shift-over to skills and attitudes that make for a good consumer or a 'global citizen', which would require learning English, computer skills and so on as early as possible. If one follows the Constitution, the values to be promoted should be those of democracy, equality, debate and free speech, scientific temper, secularism, human rights and so on.

In the drafting process before it became an Act, one view was that the bill should confine itself to infrastructural and management aspects and steer clear of transactional concerns. That was contested by another view, one that I supported, that the bill must minimally lay down principles to be followed for content and process of education. Finally, the chapter on content and process that remained in the bill requireed curriculum design institutions to adhere to principles that promote constitutional values, use pedagogic approaches based on discovery, exploration and activities, free the child from fear and trauma and promote the use of mother tongue.

Mental harassment and physical punishments of the child are explicitly prohibited.

The final version of the bill called on all unaided and special schools like the Kendriya and the Navodaya Vidyalayas to admit 25 per cent children at class 1 level from among the deprived sections of society from their neighbourhoods for free education till class 8. Their expense would be remitted to the school by the concerned government at its per learner cost or the cost the school charges, whichever is less. In addition, no school can charge capitation fees and will be punished if they do so, nor can it use any admission procedure like interviewing children or parents, except using a random method.

Illegal for a child to not be in school during school hours

Image: Students pray for rain in AhmedabadPhotographs: Amit Dave/Reuters

The Act makes an important departure in the definition of the term 'compulsory', as provided in Article 21A governing fundamental rights. The customary definition is to place the onus on parents to ensure that they admit their children in schools, and to provide for punishment of parents in case they fail to do so. One argument in favour of this provision is that this should prevent parents from engaging their children in child labour.

The Act, however, takes a completely different view and squarely puts the compulsion on governments to provide for every child to complete eight years of compulsory schooling. This implies that if a child is on the streets, working in a shop, or is simply at home at a time when he/she ought to be in school, the responsibility is of the government and it is the government that ought to be punished. This has major implications regarding child labour. Now that it has been enacted, it will be illegal for a child to not be in school during school hours, which curbs all forms of child labour during those hours.

However, the Act is silent on what the child should do after and before school hours. Similarly, it does not specify which person/agency will be legally culpable if a child is working and not in school.

This is where the legislation is at its weakest, in the matter of enforcement. It provides that in case of a complaint regarding the violation of any of its provisions, it will first go to the local authority. The problem is that the complaint will be decided upon by the very agency that is responsible for the purported violation. Though the Act does invoke the National Commission for the Protection of Child Rights and the state commissions as authorities to look into complaints, they are all distant from the sites of the complaint, normally a village.

The Act does not explicitly spell out the quantum of punishment for violations -- be it for denying admissions or violating the provisions regarding quality of access, teacher attendance and so on. For example, the Act explicitly says that admission cannot be denied for the lack of a birth certificate, transfer certificate or for seeking admission after the session has started. But who will monitor that? Will the local authorities hear the parents?

Revenue of liquor sales to be source of funds?

Image: Students of a government-run school in HyderabadPhotographs: Krishnendu Halder/Reuters

The usual argument, ever since Gandhiji's call in 1937, is that legally ensuring universal compulsory education is beyond the economic capacity of the State. Gandhiji was horrified when he was told that if he insisted, the only source of funds would perhaps be revenue from liquor sales!

Yet, despite a much better economic situation than during Gandhiji's time in 1937, the response of the government was no different.

Ultimately, a change was made in the bill that seems to have satisfied the otherwise reluctant Planning Commission and finance ministry. The Act enables the central government to make a request to the President, under Article 280 of the Constitution, to direct the Finance Commission to make allocations directly to a state for funds required for the implementation of the provisions of the act.

Hopefully, this should be favoured by the state governments since it opens an avenue for direct central funding to the states, on the basis of their requirements under the Act and reduces their crippling dependence on the vagaries of a central scheme.

The Act also overrides all the existing state legislations dealing with elementary education.

History has shown that successive governments, in spite of their constitutional obligations, do not find spending money for universalising quality education politically compelling. Could that change now?

Viond Raina is a founding-member of Eklavya, an organisation advocating alternative education. He has been one of the staunchest supporters of the Right to Education Act.

article