Photographs: India Abroad archives

So many flashbacks go past my mind's screen:

Indira Gandhi, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Ashok Mehta convivially participating in the meetings of the National Integration Council's committee on communalism, often held in 1961-62 in her father's Teen Murti Marg house at her invitation;

Indira Gandhi and Jayaprakash Narayan gaily chatting when the labours on the all-party committee on defections were done;

Indira Gandhi at her first conference of chief ministers in February 1966, arriving late and being told by Home Minister Gulzarilal Nanda that the CMs had unanimously advised the continuance of the Emergency declared in 1962 following the India-China war), responding resoundingly: 'Gentlemen, I don't agree!' (the stunned silence lasted for more than the traditional two minutes);

Indira Gandhi and Morarji Desai sitting side by side and day after day in the Lok Sabha and frequently and intensely putting their heads together...

Nothing in the character and personality of Indira Gandhi as I had known her suggested any sort of inhumanity and insensitivity. On the contrary, everything that I had known pointed to a person in the active-positive category of leadership, of delicate sensibilities, concerned with the human aspects of a situation.

Even though she herself disclaimed any special consideration as a woman and called herself a person with a job to do -- she tilted towards woman's lib just enough to use words like chairperson -- she did exemplify womanhood at its best: gentleness, softness of speech and refinement.

To me, her decision to impose the internal Emergency in 1975 was evidence of her intrepidity, a willingness to take the bull by its horns without quailing and without fear of consequences. So was her unfalteringly grasping the Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale nettle once it was clear that he had defiled the sanctity of a holy temple by amassing arms for an eventual mounting of subversive activities from within its sanctuary.

Until the mid-seventies when the iron entered into her soul and she duly became an iron lady, Indira Gandhi was fun to work with and for.

She was the first to fly to Assam in its hour of need in 1962, and the only leader of the north to rush to Madras during the widespread disturbances over Hindi in 1965 and apply her healing touch. (The south, being less unbalanced and more intellectually mature than the north, remembered Indira Gandhi for this gesture and for the many shining attributes of her vision and catholicity. That was why it solidly stood behind her in the polls held in March 1977, when the whole of the north forsook her.)

Among the memorable opportunities I had of working with her closely was my membership of the War Publicity Group constituted in 1962 soon after the Chinese invasion. She chaired the group, and provided the inspiration for formulating the first-ever psychwar (psychological warfare) strategy for the country, with unerring instinct for what would make for a telling mass media campaign against Chinese perfidy.

Bangladesh's birth pangs

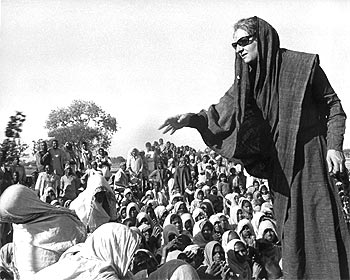

Image: Outside the Canadian parliament in OttawaWhen I was divisional commissioner of North Bengal in 1971, with my headquarters in Jalpaiguri, nearly six million refugees from East Pakistan poured into the five placid districts under my charge.

Indira Gandhi visited the camps set up for the refugees a few times. Once, I was accompanying her in heavy rains holding the umbrella in one hand and firmly gripping her arm with the other, as the ground was treacherously slippery.

She obviously wanted my hand off her, but conveyed it beautifully: 'Mr Raghavan, the only effect of your taking hold of me is going to be that when you slip and fall, you are going to pull me down also.'

At least one of her visits was in the thick of the monsoon -- to identify herself with the sufferings of the homeless. It was really hell; cholera had broken out and we had to walk through the slippery slush of faecal matter.

We took care of the refugees from East Pakistan so well and at enormous expense that visitors from abroad like Senator Edward Kennedy could not contain their admiration. Ted Kennedy in fact told me that managing such an unimaginably massive operation would have been beyond the US.

The declaration of Emergency

Image: With father Jawaharlal Nehru and sons Rajiv, right, and SanjayIt was most unfortunate that just at that time, the Allahabad high court judgment should, by one of those quirks of fate, have drawn a red herring, muddling up thinking and making a logical and objective analysis of the situation impossible.

I affirm that even if there had been no election petition by Raj Narain and no Allahabad high court judgment, conditions in India were precarious and the country needed to be pulled out of the economic, industrial and political abyss, and the only way to do it was what Indira Gandhi did, and what only she was capable of doing.

My relations with her soured slightly when, as chief secretary, Tripura, during 1975-77, it fell to me to convey to her accounts of the misgovernance by Sukhmoy Sen Gupta, the chief minister of her party there.

Her wrath boiled over when in 1977, after she was thrown out of power, I committed the cardinal sin of serving as the member-secretary of the L P Singh Committee set up by the Janata Party government to go into the working of the Intelligence Bureau and the Central Bureau of Investigation during the Emergency of 1975-77.

She never forgave me for it, although outward appearances and courtesies were maintained, and she even made me a member of the delegation led by her to the Commonwealth Heads of Governments Meeting in Melbourne in 1980.

The vindictive streak in her asserted itself soon enough, however, resulting in her vetoing the proposal the Cabinet secretary had sent to promote me to the post of secretary in the ministry of petroleum and chemicals. Luckily, this did not affect me because I was offered the post of policy adviser in the Food and Agriculture Organisation, left for Rome, and did not return until after her assassination in 1984.

She was a complex personality

Image: With US President Ronald ReaganAgain, in such meetings that are usually dominated by the old venerable, she would turn towards the young officers sitting at a distance and ask them: 'What do you think?' This she did, not patronisingly but with a genuine solicitude for their participation, and often accepted their advice even when it flew against that of their seniors.

At no discussion did she express annoyance or irritation at what was said, however unpalatable; in fact, she listened without interruption and with deep interest.

Modern-minded, result-driven, youth-oriented, was Indira Gandhi also egotistic and power-hungry and did she let her blind love for her son, Sanjay Gandhi, damage national interest and her own reputation?

Could she, of such refined breeding, lie and indulge in self-aggrandisement? Did she, whose growth from an inarticulate and shaky start (goongi gudia; dumb doll was how Ram Manohar Lohia initially characterised her) to acknowledged international stature was the marvel of self-development, so completely lose her delicacy of feeling, sensitiveness of temperament, as not to take notice of the depredations -- at Turkman Gate, for instance -- unleashed by Sanjay Gandhi and Bansi Lal?

It is hard to tell, for many villains and desperadoes have worn a beguilingly innocent mask.

My own judgment of Indra Gandhi is that she knew the meaning of power and the manner of acquiring mastery over it -- which is not a mean or sordid thing to say of any competent leader of world class. Anyone who wants to achieve has to know how to wield power in the best sense of the word.

Indira Gandhi's failure lay in not comprehending the ramifications and byways and capillaries along which power flowed, and the nasty consequences of not directing it along the right lines or controlling it when required.

It was not that she did not know or care, but simply that she saw her aberrations, not cumulatively or in a connected sequence, but in isolation and left them at that as of little consequence.

One side of a tantalising triangle

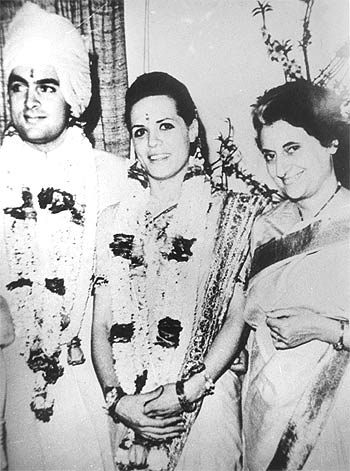

Image: At Rajiv Gandhi and Sonia Maino's weddingThe youth movements he launched in Bihar and Gujarat in the early 1970s made Jayaprakash Narayan the antipode and antidote to Indira Gandhi. This is one of the ironies of history because, as he himself stated ever so often, his emotional links with the Nehru family were strong and abiding, and came out into the open despite himself -- witness his benediction to Indira Gandhi when she met him at Patna soon after the massive electoral defeat she suffered in 1977.

JP's name and fame as a patriot who advocated adherence to principles and purity in public life had been of long standing. His perennial concern for the freedom of the individual, combined with his unremitting campaign for value-based politics, made him a national hero, comparable to Nehru in stature.

With the courage of his convictions, he espoused an accord with Sheikh Abdullah and the withdrawal of the conspiracy case against him at a time when this was considered heretic and anti-national, and even dangerous.

It shows the essentially the tolerant temperament of Indira Gandhi that she decided to draw on his idealism by making him a member of the All-Party Committee on Political Defections.

In my capacity as the secretary to the committee, I had prepared a few papers from which it was clear that right from Independence, it was the Congress party that had been responsible for the implanting of the aya ram-gaya ram culture in the body politic. She not only accepted my conclusions gracefully, but even permitted me to distribute my papers to the members of the committee.

It was her suggestion that I should keep JP fully in the picture and consult him freely. Accordingly, I met him a number of times at the Friends Colony residence of J J Singh (who had organised the India League in the US) to take his guidance on issues coming up before the committee.

My one disappointment was that he attended only two of its seven sessions and of the two, only one could be called participation in the sense that he delivered a long and ringing discourse noted for its high moral tone, and then practically fell silent without using his moral authority to channel the committee's deliberations along the lines desired by him.

However, one proposal that he made would have made a vital difference to the quality of India's elective bodies: the idea of incorporating in the Constitution a provision for recall of legislators who were found to be worthless, wayward, incompetent or corrupt. The committee lost no time in rejecting it out of hand.

To my mind, JP remained a man of noble thought, spurning anything by way of deep involvement in charting a determined course towards bringing it to fruition. True, in symbolising the will of the parties opposed to the Congress and putting heart into them to struggle free of the crippling restraints placed on them and in giving tongue to libertarian values at a critical juncture, he rendered a service that stood on its own.

But when the memory of the tumult and tantrums of those days fade, whether he will remain little more than a cherished memory is a question best left unanswered.

The third side of the triangle

Image: Bangladesh leader Sheikh Mujibur Rehman introduces Indira Gandhi to his cabinetHis spirit, like Banquo's ghost, still haunts political party forums especially in Tamil Nadu, where Kamaraj Rule is looked upon as some kind of analogue of Ramarajyam.

Next to Gandhiji, he was the one leader who was quoted or misquoted by politicians of widely incompatible hues, beginning with the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam at one end and the leading lights of non-Congress parties in the north on the other.

I saw him in action as a member of the Committee on Regionalism, of which C P Ramaswamy Aiyar was the chairman and Biju Patnaik, Y B Chavan, B P Chaliha and Ashok Mehta were the other members.

He certainly deserves the reputation that he enjoyed for political shrewdness and uncommon common sense.

He stage-managed the Committee's interviews at Madras in September 1962 so very well that I was left dumbfounded at the skill and mental agility of a man of little formal education who was not at ease with English and was ignorant of Hindi.

The Committee was casting about to find a way out of the incipient secessionist demands such as that of the DMK for Dravidasthan, when Kamaraj came up with the brilliant idea of a Constitutional amendment requiring every candidate for election and every elected representative to take an oath pledging to uphold the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India, with the concomitant implication of instant disqualification of the party, the candidate and the elected representative violating the oath.

With one neat and simple stroke, Kamaraj's brainchild applied the quietus to all such treasonable activities.

At one of the conversations I had with him, I happened to express the view that the Dravidian movement deserved credit for inculcating self-pride in the Tamils, reviving the past glory of the Tamil language and culture, weaning the people from blind superstitions, and fighting the inequalities and inequities of caste.

Kamaraj spluttered into expletives, the substance of which was that it was all monumental hypocrisy -- the Dravidian parties were a curse and Annadurai was ... well, I leave out his comments since they would hurt those who extol him as the last word in wisdom and erudition.

I was fortunate to be around when he made a decision that was to become a historic turning point of Indian politics. As every school boy knew, when Kamaraj came to a decision, it was his mannerism compulsively and rapidly to untie and tie his lungi -- loosen, tighten, loosen, tighten -- like that! Lal Bahadur Shastri had died at Tashkent and Kamaraj -- on demand for a second time as a king maker -- was flying to Delhi with a horde of other politicians from Madras.

I was also right there at the airport and saw Kamaraj nervously, all by himself, pacing the verandah and untying and re-tying his dhoti! I stealthily got behind him and paced in step.

Kamaraj was muttering to himself. I lent my ears. Guess what the perunthalaivar (Great Leader) was chanting: Indira Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, Indira....!

B S Raghavan has worked directly with three prime ministers -- Jawaharlal Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri and Indira Gandhi

article