Photographs: Adnan Abidi/Reuters A Ganesh Nadar

In India, water riots have broken out in Madhya Pradesh this year and people have lost lives fighting over water in both MP and Rajasthan. Every time the Cauvery issue flares up between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, property worth billions of rupees has been destroyed in both states. Inter-state buses and lorries are blocked causing more hardship to the people and further loss to trade and the exchequer.

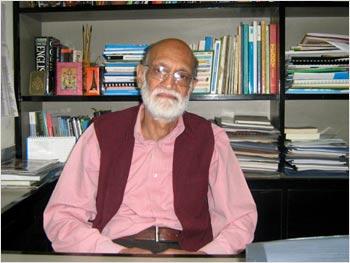

Water is divided among seven ministries at the Centre and thus no one really gives it the importance it deserves, bemoans Ashok Jaitly, a retired IAS officer of the Jammu & Kashmir cadre and the state's former chief secretary.

An authority on the complex intricacies of Kashmir and a noted observer on Pakistan, he now brings his skills to the much ignored issue of water shortage in the country.

With a Master's in economics and a diploma in development studies from Cambridge University, Jaitly has over 40 years experience at senior management levels in various central and state government departments. He is currently the director of water resources at The Energy Resources Institute in New Delhi, whose director general is climate change guru Dr Rajendra Kumar Pachauri.

He spoke to rediff.com's A Ganesh Nadar about the severe water crisis in the country and the chalta hai attitude of both the government and the people.

How serious is the water situation in the country?

I do not want to sound like an alarmist, but it is very bad. Whether you look at it from the irrigation side, the drinking water side, the waste-water management side, we are facing shortage in critical areas and there is tremendous amount of inefficiency in its management.

I don't want to exaggerate, but it is a very, very serious situation.

How serious will it get?

It is already very serious. It will get worse if we continue to behave like it is business as usual. At all levels at the central, state official level and the people's level, we are not treating it as seriously as we should.

We should manage our water resources much more carefully. Not wasting water, paying for water. Issues people are not willing to face candidly, frankly and seriously. It is going to become much more serious.

What is the solution?

There are a number of solutions, it's not as if there are no solutions. I will not be giving any new solution. Everyone knows the solutions. A water policy was enunciated in 2002. How much of it is being implemented?

In irrigation 40 to 50 per cent of the water is being wasted. We have to reduce that. It is both technical wastage and managerial wastage. We don't have the money to repair irrigation channels. When you over exploit ground water somebody else will be affected.

Even in urban water supply there is so much wastage. Take, for example, Delhi. The water board admits that they lose 40 to 60 per cent of the water. Obviously better management, better regulation, is needed.

The frameworks have to be looked at. The economics have to be looked at. You cannot have a pricing where you cannot recover operational and maintenance costs. People are not willing to pay, farmers are not willing to pay.

We have governments saying, 'We will give free electricity for ground water extraction.' With the result you are encouraging wastage of water. It's the same with urban areas. The poor people pay more for water than the rich. The rich get greater supply from the main lines and pay lower tariff. And the poor have to supplement their water needs with tankers or somewhere else and thus end up paying more.

'Many senior politicians don't want to go to the ministry of water resources'

Image: Ashok JaitlyPhotographs: A Ganesh Nadar

It is still on the planning board. It is very difficult to say if it is viable or not. In principle you can say we should transfer water from a surplus region to another. It is too costly, the technology is complicated and the environmental damage is still not known.

There is a natural flow of water and you are interfering with that flow. To change that flow you will have to go through mountains and hills and so on. Is the environmental cost valid?

We have to do a much deeper analysis of it from every aspect on how people are going to be impacted.

Similarly the element, which is unknown today, is the climate change aspect. We have glaciers melting and the Ganga and the Brahmaputra will be affected with lower flows. Then there will be no surplus water to transfer.

There may be an urgency in the need, but decisions cannot be taken in a hurry. This decision might prove very costly for future generations if we make the wrong decision. And it will be very difficult to reverse.

Why does the government treat water so shabbily?

Parliamentary Affairs Minister Pawan Kumar Bansal is also the water minister. I don't think many senior politicians want to go to the ministry of water resources. It doesn't have a large budget and the other aspect is that the minister deals with a very small part of water. Only irrigation.

Urban drinking water is with the urban development ministry.

Rural drinking water is with rural development. Hydel generation is with the ministry of power.

Low hydel power is with the ministry of renewable energy.

Watershed development is with the ministry of environment and forests.

Minor irrigation is with the agriculture ministry.

I have been arguing that the government should rationalise this and put all water management under one ministry. Make it the focal ministry and give it to a very senior minister and give it the importance that is its due.

Water riots have occurred in Bhopal. People have been killed over water. Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra are a few of the states that fight over water. When and how will this end?

Water riots also occurred in Rajasthan on the Indira Gandhi canal 5, 7 years ago in Ganganagar. Seven people died in 2002 if I am not wrong about the year. Tamil Nadu and Karnataka have been fighting over the Cauvery water for how long?

It is potentially ridden with conflicts. Big farmer versus small farmer, urban versus rural. Agriculture and industry are all competing.

We have to bring people together and have dialogues.

Water is a state subject and the Centre doesn't have control over water. I am not recommending central control. We must find a mechanism that enables the Centre to make agreements between states. The long drawn out court cases, tribunals do not help. There are inter state councils, there is a national council. These bodies must come together on a matter as important as water.

There must be a national consensus. It is time there was strong public pressure to push the political leadership to come to a consensus.

In Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, they got the farmers together and it worked for a while. That has to be continued and for the media to put pressure on the government, it should create public opinion, create awareness.

What about private bottling plants in water starved states?

We did an independent study of all the plants of Coca-Cola. Out of four, three had no problems. The one in Rajasthan there was some problems and we suggested remedial methods. But if we study any industry which uses water you will know that the water usage is less.

Eighty five per cent of water is used for irrigation. Even in industry the beverage industry is very small.

The big consumer in industry is thermal plants. Thermal plants account for 70 to 80 per cent of the water usage by industry. They use it for cooling. They are conscious of it. They recycle the used water. Now there is a new technology of dry cooling. There are coolants.

'1,700 crores have been spent on cleaning the Ganga, 1,000 on the Yamuna'

Image: Slum dwellers carry empty containers during a protest in Chandigarh.Photographs: Ajay Verma/Reuters

Very, very far because it is too sensitive an issue. And there is no proof anywhere in the world that privatisation of water makes the distribution or storage any better or more efficient. They have done it in Jamshedpur and it is working very well there.

There is already privatisation. Chennai gets 60 per cent of its water from tankers. The state government has taken these tankers on lease and pays them. So Chennai has brought them under control.

Chennai also has a 100 million litres per day desalination plant coming up. They have done a good job with water harvesting. Gujarat is putting up a big plant. The cost of desalination is also high. Other cities will also have to go for it. There is no option.

Irrigation is private and large farmers are selling water to small farmers. We do not want privatisation as a matter of policy and ideology, but it is happening all around.

We have to think of the best way to manage it. We have to face reality, brushing it under the carpet is not going to help.

What about pollution of water bodies?

The pollution board can haul up any industry. The minute they issue a notice the fellow goes to court and gets a stay.

Inspite of billions of rupees going down the river in the name of cleaning, the Ganga and Yamuna are still dirty?

Rs 1,700 crores (Rs 17 billion) on the Ganga alone and Rs 1,000 crores (Res 10 billion) on the Yamuna. Both rivers have become worse. Obviously, money is not a problem. But it is a managerial one.

Now they have action plan 2 for Yamuna. Plan 2 won't work too. The treatment has to be integrated. Not piecemeal. The whole river has to be cleaned together and further pollution has to be prevented.

How do you maintain the quality of drinking water?

It is a serious problem. A large percentage of infant mortality is due to water borne diseases. We need a massive campaign to teach people how to clean water in a low cost method. Like sand filters, charcoal filter. It has to be at the panchayat level.

The charcoal will remove many minerals, but you cannot expect it to remove fluoride or arsenic. For that you need proper treatment.

But this basic cleaning will go a long way in improving health standards.

article