Photographs: Fayaz Kabli/Reuters Ajai Shukla in New Delhi

On Thursday, the BJP and the Shiv Sena appeared before the Election Commission to allege that Electronic Voting Machines, which are now used for all Indian elections, can be manipulated to favour a candidate.

But old-timers from Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL), who perfected the EVMs in the late 1980s, say that all the current allegations have been raised before, and comprehensively disproved.

Colonel H S Shankar, former Director (R&D) at BEL, says that EVMs came under fire soon after BEL demonstrated these to Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in mid-1989. Shankar, who attended that meeting, recalls that an impressed Rajiv Gandhi suggested the use of EVMs in 150 constituencies during the 1989 general elections.

Revisiting the EVM controversy

Image: An officer holds a mock electronic voting machine as he explains the counting procedure to staffPhotographs: Punit Paranjpe/Reuters

The first challenge came swiftly. On October 15,1989, at a dramatic press conference in New Delhi, Janata Dal chief, Vishwanath Pratap Singh and George Fernandes produced a "computer consultant" to prove that EVMs could easily be rigged.

Before a crowd of journalists, the consultant keyed in "3 + 3" into a computer, pressed "Enter" and showed the answer to the crowd. It was 9.

In the charged atmosphere of 1989, the Election Commission scrapped the plan to use EVMs that year.

But when V P Singh became PM, BEL launched a campaign to prove the reliability of electronic voting. Eventually, the government created an experts committee to examine whether EVMs could be "fiddled".

Revisiting the EVM controversy

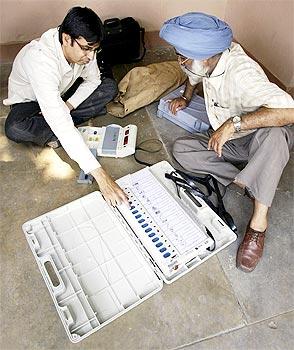

Image: Polling officers check an EVM at a distribution centrePhotographs: Munish Sharma/Reuters

Professor S Sampath of the Defence R&D Organisation headed the committee, which included Dr P V Indiresan of IIT Delhi, and Dr C Rao Kasarabada, Director Electronic Research and Development Center, Trivandrum.

Dr Indiresan gathered four of his brightest research students and gave them five days to subvert the EVM's source code. Their only restriction: there should be no external damage to the EVM.

Colonel Shankar says that BEL gave Dr Indiresan's team all the EVM circuit diagrams and design drawings; only the encryption-coded software was withheld. "After five days of struggling, they admitted that the EVM was tamper-proof."Revisiting the EVM controversy

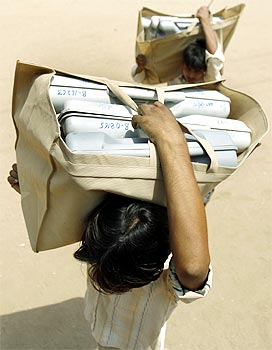

Image: Workers carry electronic voting machines from a distribution centrePhotographs: Punit Paranjpe/Reuters

At the core of the EVM is a micro-controller chip, built by Hitachi of Japan, called an OTP-ROM (one-time programmable read-only memory).

Onto this, the Indian EVM contractors -- BEL and Electronics Corporation of India (ECIL) -- "burn" the algorithm that makes it record votes. The microprocessor's "non-volatile" memory ensures that, once the algorithm is written, it can never be overwritten or subverted, not even by the manufacturer.

The algorithm makes the EVM function as a vote counter. Each candidate is assigned a numbered button, according to the alphabetic order of the candidates' names.

Each time a voter presses, say, Button No 1, the software adds one vote to the account of Candidate No 1. And since, in each constituency, each political party's candidate will have different serial numbers (determined by the candidate's name), there is no possibility of installing a countrywide code that favours one party.

Revisiting the EVM controversy

Image: An official holds an EVM displaying the number of contested candidates during the counting of votesPhotographs: Fayaz Kabli/Reuters

After failing to subvert the software, the Sampath Committee staged a mock election to try and subvert the procedure. Failing to do so, it strongly endorsed the EVM.

Chief Election Commissioner, R V S Peri Sastry, discussed the test results with all the political party heads, including BJP President L K Advani, all of whom agreed to the use of EVMs in general elections.

"The reason why all parties accepted the EVM was simple", explains Colonel Shankar, "We copied the simplicity and transparency of the earlier system, while doing away with its drawbacks."

Revisiting the EVM controversy

Image: Technicians check EVMs at an election officePhotographs: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

Besides the tedious counting of votes, the major drawback in the old system of paper voting was booth capturing.

Party goons would take over voting booths and, in a couple of hours, stamp thousands of paper ballots in each booth and slip them into the boxes.

EVMs mitigate the effects of booth capturing, since a delay circuit ensures only two votes can be recorded per minute. Even if a booth is captured for an hour, a maximum of 120 votes can be polled.

EVMs were used for the first time in general elections in 45 seats in 1999. Polling in the 2004 general elections was entirely on EVMs. This year, again, 671 million voters got the opportunity to vote on EVMs.

article