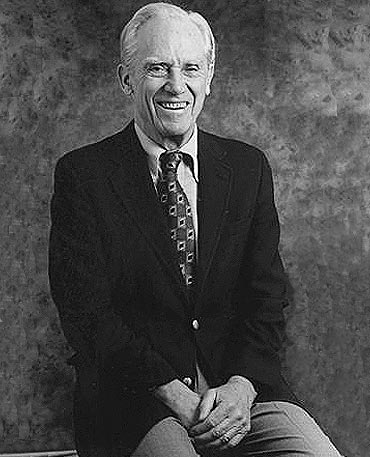

Carl E Taylor, an internationally reputed healthcare expert born in Landour (now in Uttarakhand) and a lifelong lover of India, died in the United States last month of prostate cancer.

Carl E Taylor, an internationally reputed healthcare expert born in Landour (now in Uttarakhand) and a lifelong lover of India, died in the United States last month of prostate cancer.

Taylor, 93, the founding chair of the Department of International Health at Johns Hopkins, where he taught for nearly 50 years, dedicated his life to the well-being of the world's marginalized people, including in India, which he called home.

So attached was he to India, where he was born to his doctor parents, that Taylor visited India in the summer of 2008 at the age of 92 to help villagers identify and address health issues.

"My dad had great hope for India," said Daniel Taylor, his son who is the president of Future Generations, an international school for communities offering graduate degrees in applied community change and conservation.

"He was deeply committed to the welfare of the poor in India. Where others saw great need, he saw great potential as he had walked with them through their magnificent achievements of the independence movement to the extraordinary progress of participating with simple village women who were able to bring down mortality by 70 percent simply by their action."

Carl E Taylor worked in over 70 countries and had students from more than 100 countries. He taught students till a week before his death.

His career began at age 7 as a pharmacist assistant in his parents' oxcart-based clinic in the jungles in India. His childhood was spent in those jungles, before going on to earn his medical degree from Harvard. His medical school application opened with the words: 'My study of anatomy began dissecting a tiger to see where the food went.'

Following medical school, he worked in Panama where he married his wife of 58 years, the late Mary Daniels Taylor, who died in 2001 and was professor emeritus of education at Towson University.

Taylor returned to India in 1947 as director of Fategarh Presbyterian Hospital where he led a medical team through the deadly riots of 1947 during the Partition of India. In 1949, he conducted the first health survey of Nepal, then the most closed country in Asia.

"My grandparents were under the Reformed Presbyterian Mission Board, which I believe later became part of the Church of North India," Daniel explained. "They, along with my father, lived later in Roorkee, Uttar Pradesh.

Turning over the mission hospital when it was able to be run by others, they made a regular circuit of the villages by oxcart to take clinical services to the rural people. Helping dispense medication, or roaming the Himalayan hillsides, gave my father a deep appreciation for the needs and resources of India's people."

At Harvard, Taylor completed his MPH and DrPH degrees. His doctoral dissertation provided the seminal research that defined the synergism between nutrition and infection, today a principle at the foundation of public health. In 1952, he founded the department of preventive medicine at the Christian Medical College Ludhiana, the first such department in the developing world.

"My father used to say that no health-care system is a vacuum, accepting the prior existence of other systems of healing other than allopathic medicine," Daniel said. "At the same time, his research confirmed that commercial exploitation of the people resulted in bad health outcomes, whether it was the pharmaceutical industry or unethical traditional healers."

Taylor was instrumental in designing the global agenda for primary health care in the 1960s and 1970s. Before it was widely embraced, he was part of research and movements that connected women's empowerment and holistic community-based change.

Throughout his life, Taylor had particular interest in health-care reform, especially the integration of services.

His research achievements were wide ranging. The Narangwal Rural Health Research Project in northern India, which he led from 1960 to 1975, provided breakthrough understandings in the diagnosis and treatment of childhood pneumonia, neonatal tetanus, getting medical care to the villages, synergism of malnutrition and child mortality, understanding childhood diarrheal treatment and community empowerment for lasting health solutions.

Henry Taylor, the other son of Taylor's three children, who is a senior associate, Department of Health Policy and Management at Johns Hopkins Preparedness Programs, said the Narangwal Project developed the scientific way to train community health workers to provide the most basic care needed at the village level. The project was closed down due to the war with Pakistan, but those involved have spread its message to hundreds if not thousands of other projects around the world.

"He was deeply disturbed by how India's healthcare system was a sickness care system centered around making money for the providers and not providing health for the people. He spent decades of his life pointing to practical alternatives," said Daniel.

In addition to his 48 years at Johns Hopkins, Taylor was China representative for UNICEF from 1984 to 1987. From 1992 until his death, he was senior adviser to Future Generations and more recently Future Generations Graduate School where a professorship is endowed in his name. From 2004 to 2006, he was Afghanistan Country Director for Future Generations, where he led field-based action groups using over 400 mosques as educational sites for Afghan women. He returned to Afghanistan in 2008 to test hypotheses about how 'women can in action groups solve the majority of their family health problems.'

From 1957 through 1983, he advised WHO on a wide range of international health atters. In 1972, he became the founding chair of the National Council for International Health, now known as the Global Health Council.

He was also the founding chair of the International Health Section of the American Public Health Association. He received honorary degrees from Muskingum College, Towson State University, China's Tongji University, Peking Union Medical College and Johns Hopkins.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton recognized him for 'sustained work to protect children around the world in especially difficult circumstances and a lifetime commitment to community based primary care.'

In the last year of his life, he was sitting with women in a bamboo hut in northeast India asking them how they would shape their futures, when they responded, 'it is harra, empowerment of ourselves.'

"India was always his home," said Hanry Taylor about his father. "He loved the people, the excitement, the challenges, the resourcefulness, and also the mangoes. It is true he loved mangoes, but maybe not appropriate for you to write when you are writing an obituary."